In our movement for a just democracy, we often affirm that data and technology, in the hands of oppressed communities, can help liberate us. The life and legacy of Ida B. Wells-Barnett provides compelling evidence of this truth.

Born Ida Bell Wells in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862 and often writing under the pseudonym, “Lola” throughout her career, Wells’ legacy as a courageous reporter and activist has made her a symbol of justice journalism, Black resistance, and Black feminist organizing.

Her work also proved that data is more accurate when collected and driven by communities, making her a trailblazing data specialist and storyteller.

A Lifetime of Resistance

As a Black woman who lived in the U.S. during the late 19th and early 20th century, Ida B. Wells-Barnett encountered overt anti-Black racism and sexism, often in the forms of erasure, vitriol, and violence. Over a half century before Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks refused to give up their seats to white riders during the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, Wells refused to give up hers on a train from Memphis to Nashville in 1884. She was brutally thrown off the train and unsuccessfully sued the railroad company. During the 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C., white suffragist organizers asked women of color to march at the back of the parade. Wells refused to do that too.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

— Ida B. Wells

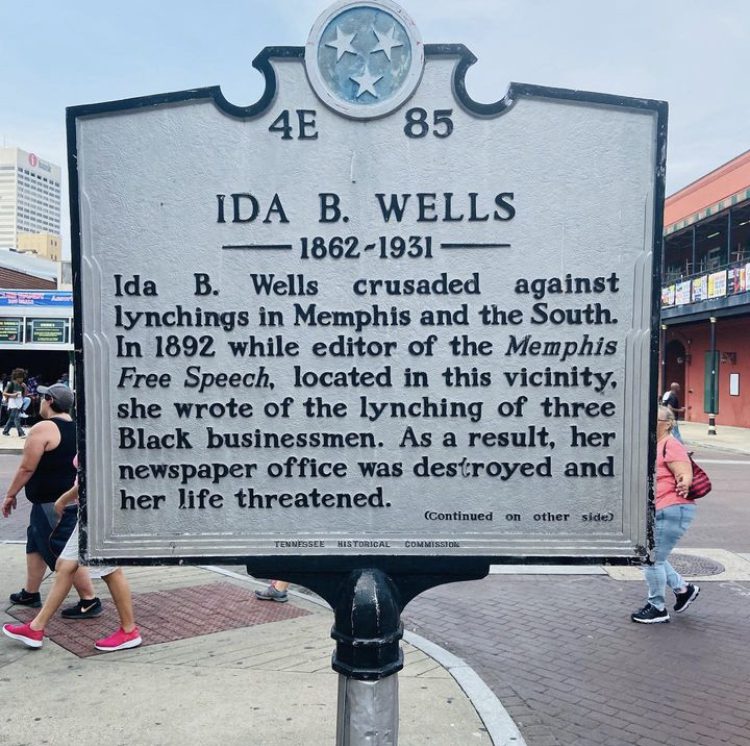

During her lifetime, Wells-Barnett organized educational and civic opportunities for Black people in the U.S., but in mainstream culture and media today, she is most recognized for her work as an investigative journalist. Following the lynchings of three Black business men in Memphis, Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart in 1892, Wells was committed to telling the truth about white supremacist terrorism in the U.S. Wells wrote an editorial in the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, where she was a co-owner, condemning lynching and citing 10 others that happened the same week as the murders of Moss, McDowell, and Steward. In it she wrote, “This is what opened my eyes to what lynching really was: an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized.”

The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) describes lynching as “an institutionalized method of social control to maintain white authority. For the perpetrators, committing and witnessing lynching served as unifying acts in forging a white identity…” In the South and in Civil War border states, lynchings were frequently attended by everyday white Americans and grotesquely treated as entertaining pastimes — and were purposefully underreported.

After Wells published the editorials, white residents in Memphis destroyed her newspaper office and threatened her life. In spite of this, Wells refused to stop reporting on lynchings. She moved to New York to continue her writing, traveled across the U.S. and internationally to spread her findings, and demanded reforms from President William McKinley.

By persistently reporting on these atrocities with as much data and detail as possible, Wells disrupted the status quo of media silence and indifference by local governments and law enforcement on racial terrorism in the U.S. Her pioneering compilation report, A Red Record: Lynchings in the United States, found that over 10,000 African Americans were killed by lynching in the South between 1864 and 1894.

Data Strengthens Our Movement

This attention to the power of data resonates deeply within multiracial democracy movements where BlPOC folks, queer folks, women, young people, and working families are leading the charge for equitable political power and representation for our communities. We know that numbers illustrate the seismic realities of systemic oppression, from the millions of people ensnared by mass incarceration to the millions of Americans currently living below the poverty line. Whether our mobilizations are around census counting, public demonstrations, voter registration, community contacts, or direct services, we know that access to accurate data results in more precise outreach that empowers communities to resist and engage.

“While data may suggest low voter turnout within communities of color, the reality is far more nuanced. Factors such as candidate inspiration, financial disparities, and external circumstances like natural disasters or cultural events play significant roles in shaping voting behavior.

— Dynisha Hugle, Data and Targeting Director of the Power Coalition for Equity and Justice

“By embracing the approach championed by figures like Ida B. Wells, which focuses on collecting data with a keen awareness of context and history, a richer and more accurate understanding of the situation emerges.”

In the last two years alone, we’ve seen meaningful progress for our movement including victories for redistricting in Alabama, reproductive freedom in Michigan and Ohio, voting rights restoration in Minnesota and New Mexico, and more. The power of data and media play major roles in making such moments possible.

“Historically, Black women were often kept out of data fields due to systemic racism, discriminatory hiring practices, lack of access to education and training opportunities, and implicit biases within organizations. It is essential to address these issues and work towards creating more inclusive and equitable spaces for all individuals to thrive and contribute their unique perspectives.”

—Jakalia Brown, Senior Data Manager at ProGeorgia

Investing in Movement Technology

In the State Voices Affiliated Network, we’re investing in more and more BIPOC data engineers, especially women of color. We’re building leadership and skills across our movement, and we’re moving towards movement-owned and movement-center technology.

“Shatira, Dynisha, Kaelyn, Jakalia, Hersheda, and Sha’Kirayah, members of Data teams across our network, are today’s ambassadors representing the State Voices data pipeline. When I joined State Voices, there were zero women data directors in our state network—now there are three, and all are women of color. — Brandon Jessup, State Voices’ Deputy Director of Data Analytics and Movement Technology.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett used data storytelling to expose the truth of racial terror in the US. She was part of a community of leaders and advocates whose work pressured white America into confronting the truth about lynching. In Wells’ legacy there is also clear attention to the interconnectedness of persistent issues facing Black Americans including state violence, voter disenfranchisement, and scarce opportunities for education and employment as well as the necessary range of tools used to organize. Wells concluded that the violence that shaped Reconstruction and Jim Crow was due to white fear of increased political power within Black communities and she encouraged Black Americans to embrace electoral organizing and exercise their right to vote.

“Within the progressive movement, there is no place for narratives, theories, or data about our communities and our movement without the voices of our people. To me, that is what data is and does: it gives voice to OUR truth, which we see more clearly and know more deeply than anyone else.”

—Hersheda Patel, Data Director of ProGeorgia

Wells-Barnett committed her life to telling stories in full, and like countless other historic women, BIPOC, and TLGBQ+ folks, hers is still being uncovered. In her journey, we see recurring themes of relentless resistance in spite of ongoing attempts of erasure. For those of us who are committed to building a world where we can all be free, we’re sure to find inspiration in her incredible courage and in her pen.

Categories: Civic Tech and Innovation, Voting Access